Описание слайда:

The Colonial Origins of Modern Institutions

International data show a remarkable correlation between latitude and economic

prosperity: nations closer to the equator typically have lower levels of income

per person than nations farther from the equator. This fact is true in both the

northern and southern hemispheres.

What explains the correlation? Some economists have suggested that the

tropical climates near the equator have a direct negative impact on productivity.

In the heat of the tropics, agriculture is more diffi cult, and disease is more prevalent.

This makes the production of goods and services more diffi cult.

Although the direct impact of geography is one reason tropical nations tend

to be poor, it is not the whole story. Research by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson,

and James Robinson has suggested an indirect mechanism—the impact of

geography on institutions. Here is their explanation, presented in several steps:

1. In the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, tropical climates

presented European settlers with an increased risk of disease, especially

malaria and yellow fever. As a result, when Europeans were colonizing much

of the rest of the world, they avoided settling in tropical areas, such as most of

Africa and Central America. The European settlers preferred areas with more

moderate climates and better health conditions, such as the regions that are

now the United States, Canada, and New Zealand.

2. In those areas where Europeans settled in large numbers, the settlers established

European-like institutions that protected individual property rights

and limited the power of government. By contrast, in tropical climates, the

colonial powers often set up “extractive” institutions, including authoritarian

governments, so they could take advantage of the area’s natural resources.

These institutions enriched the colonizers, but they did little to foster economic

growth.

3. Although the era of colonial rule is now long over, the early institutions that

the European colonizers established are strongly correlated with the modern

institutions in the former colonies. In tropical nations, where the colonial

powers set up extractive institutions, there is typically less protection of property

rights even today. When the colonizers left, the extractive institutions

remained and were simply taken over by new ruling elites.

4. The quality of institutions is a key determinant of economic performance.

Where property rights are well protected, people have more incentive to

make the investments that lead to economic growth. Where property rights

are less respected, as is typically the case in tropical nations, investment and

growth tend to lag behind.

This research suggests that much of the international variation in living standards

that we observe today is a result of the long reach of history.

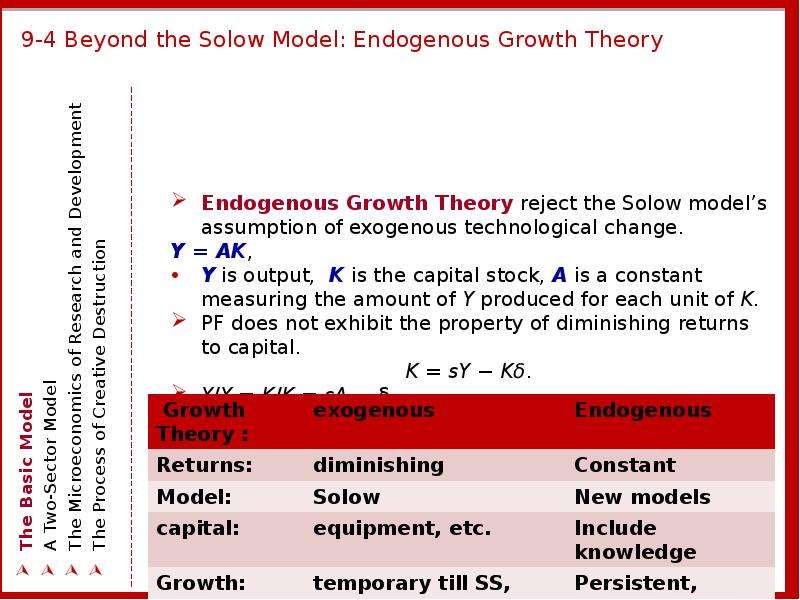

![9-4 Beyond the Solow Model: Endogenous Growth Theory

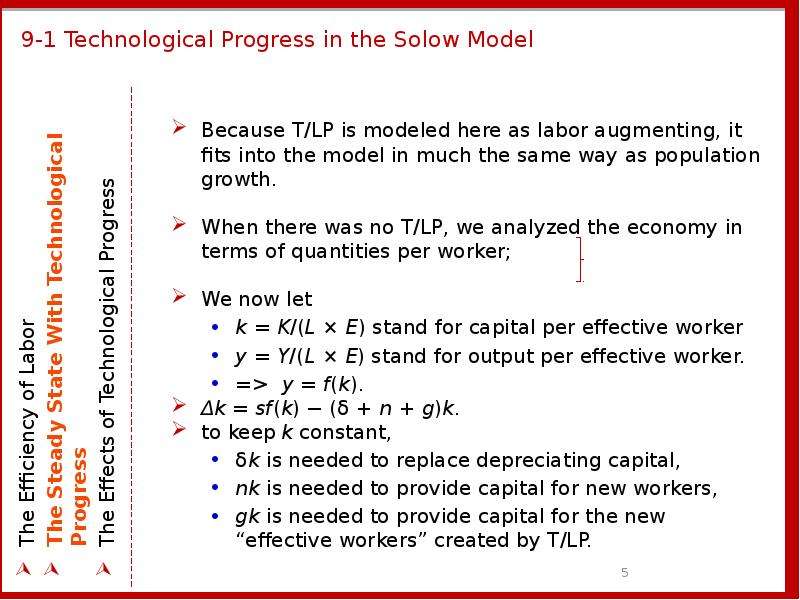

Y = F[K, (1 − u)LE] (PF in manufacturing firms),

E = g(u)E (PF in research universities),

K = sY − K (capital accumulation),

u is the fraction of the labor force in universities

1 − u is the fraction in manufacturing,

E is the stock of knowledge (efficiency of labor),

g is a function that shows how the growth in knowledge ~ on the fraction of the labor force in universities.

Assumtion:

The PF for the MF have constant returns to scale.

This model is a cousin of the Y = AK model.

This economy exhibits constant returns to capital, as long as capital is broadly defined to include knowledge. Persistent growth arises endogenously because the creation of knowledge in universities never slows down.

This model is also a cousin of the Solow growth model.

If u is held constant, then the E grows at the constant rate g(u). This result of constant growth in the E of labor at rate g is precisely the assumption made in the Solow model with T/LP.

For any given value of u, this endogenous growth model works just like the Solow model.](/documents_6/587490f2c392f9ea97c3f5d587a420ea/img25.jpg)